- Home

- Tommy Greenwald

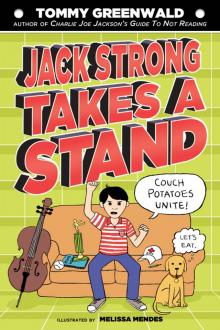

Jack Strong Takes a Stand

Jack Strong Takes a Stand Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Michele Rubin and Nancy Mercado,

for obvious reasons

And to parents and children everywhere,

who try to find the right balance every day

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Schedule

Part 1 Before

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Part 2 During

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

Part 3 After

39

40

41

42

Epilogue

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Copyright

PART 1

BEFORE

1

I was about to go to soccer practice when I decided to go on strike.

I didn’t mean for it to become this big thing.

I was just feeling kind of tired, that’s all.

But the next thing I knew, there were two big television trucks outside my house.

There was a stage on my front lawn, with lights mounted on twenty-foot poles. There was a television host sitting right next to me. There was an audience gathered in front of the stage, full of people. Half of them thought I was a hero, the other half thought I was a menace to society.

And they were all there because of me.

Just because I sat down on a couch.

Who would’ve thought?!

* * *

But first, a little background information.

My name is Jack Strong, but I used to wish it wasn’t.

I know, it sounds like a cool name. And it would be a cool name, if I actually were strong. But I’m not. Just lifting my ridiculously heavy backpack in the morning is a challenge.

The truth is, I’m kind of weak.

Which the other kids think is hilarious, of course.

I go to Horace Henchell Middle School. It’s a typical middle school. The classrooms are way too hot, and the cheeseburgers are way too cold. No one knows who Horace Henchell is, but it’s generally assumed that he is both well respected and dead.

I do really well at the school part of school. My grades are excellent, and the teachers like me. I don’t make trouble.

The non-school part is a little harder for me. I’m not what you would call a loser or anything, but I’m definitely not at the top of the heap, either. I’m in that huge middle section of kids who mind their own business and try to get through the day without any real drama. Usually it works. I’m not a great athlete, and I don’t think the modeling agencies will be calling anytime soon, but some people seem to think I’m pretty funny. Every once in a while I make a joke in class that the other kids laugh at, and that’s enough to keep me off the list of dorks and lame-os, at least for the time being.

I have one really good friend, Leo Landis, who I’ve eaten lunch with every day since second grade, and one really bad enemy, Alex Mutchnik, who’s hated me ever since he was caught cheating off my math quiz last year. (I didn’t tell on him, but he hates me anyway.) Alex’s favorite activities are knocking my backpack off my shoulders and gluing my locker shut.

You know, typical school stuff.

But I definitely don’t hate school. There’s a lot about it that I like.

For instance, there’s Cathy Billows, who’s so pretty that it makes my eyebrows hurt. There’s Mrs. Bender, my favorite teacher, whose tiny but unmistakable mustache makes me smile every time I see it.

And there’s the bus ride home.

The ride home is incredibly important because it’s the one time of day I have completely to myself. I always sit in the same seat: third row back, window seat on the left. The seat next to me is usually empty, but I don’t mind—it gives me a place to put my backpack. And as the bus slowly rolls away, I gradually begin to put the school day behind me.

“Have a nice night, Horace,” I say. And then—using my jacket as a pillow—I rest my head against the window, smile, close my eyes, and think about my absolute favorite thing in the world.

The couch.

* * *

To someone who doesn’t know any better, our couch is no great shakes.

It has one or two rips in it, from when my dog, Maddie, makes herself comfortable a little too aggressively. It has plenty of stains—soda stains, sauce stains, chocolate stains, and several mystery stains. And it might not surprise you to learn that it smells a little, too. My mom always talks about getting rid of it, but I won’t let her.

Because to me, that couch represents everything good.

It’s where I watch Dancing with the Chimps, my favorite TV show. It’s where I play Silver Warriors of Doom II, the video game that Leo and I would happily play until we are old men, if only our parents would let us. It’s where Maddie lies down on my lap, even though she’s way too big to be a lap dog.

It’s where I daydream about Cathy Billows.

It’s where I forget about Alex Mutchnik.

It’s where I eat a huge bowl of Super Fun Flakies every day after school.

I could go on and on, but I think you get the picture. The couch is pretty much my favorite place in the world.

The only problem was the outside world kept interrupting.

Because here’s the thing: I was probably the most overscheduled kid in the entire universe. Or, at least, I was tied with all the other overscheduled kids. And there wasn’t anything I could do about it.

And then came the week of June 6.

2

It all started after school on Wednesday, June 8. I was just settling in on the couch.

“JACK!”

I prepared myself for the second blast, which was definitely coming.

Wait for it …

“JACK!”

There it was.

My mom ran into the room.

“Have you seen my phone?”

My mom is the world’s absolute greatest person, but she has two problems: she can never find her glasses and she can never find her phone. Sometimes, the fact that she can’t find her glasses means that she can’t see well enough to find her phone.

“No, Mom, sorry. I haven’t.”

She sighed. “Well, what else is new? Dad is going to kill me.” The one thing my dad can’t stand is when he tries to call my mom and she doesn’t answer. Which happens probably around, oh, let’s say sixty-two times a day.

Mom slapped my leg. “What did I say about leaving your shoes on in the house?”

“What’s the point of taking them off?” I complained. “I just have to put them back on in ten minutes anyway.”

“Still.” That was my mom’s answer for everything, when she didn’t have an actual answer.

My grandmother, whom

I call Nana, came into the room from the kitchen. Nana is seventy-four years old, but she has more energy than anyone in the family. She’s my mom’s mom, but my dad thinks of her as his mom, too, since his parents died a pretty long time ago.

Nana was eating a tongue sandwich, as usual. She loved tongue, which may be the grossest meat ever invented by man. I think it’s from a cow. She made me try it once. It was so salty my mouth dried up on the spot. It’s also bad for you. It’s especially bad for people with heart problems, like Nana, but she didn’t care.

“How can you eat that?” I asked, which was the same question I asked every time.

“You don’t know what you’re missing,” she said, which was her usual answer. “Want to watch my story with me?” A “story” is one of the daytime reruns she loves, usually old crime shows like Law & Order or Magnum, P.I. or something like that. She’s also a TV news and politics junkie, I think mainly because she loves talking about how wrong most people are and how the country is falling apart.

“I can’t, Nana. I have to go to swimming.”

Nana shook her head. “Swimming schwimming.” She looked at my mom. “Why do you make this boy run all over town doing silly things? Can’t he just sit and relax with his grandmother? Is that so wrong?”

My mom shrugged as if she’d had this conversation a thousand times, which she had. “It’s important to stay active,” she said. “It helps kids stay focused.”

“Says who?” asked Nana. “You or Richard?”

Richard is my dad.

“I don’t have time to talk about this right now,” grumbled my mom. Then she glared at me, as though it were my fault she had a mother. “Go get your bathing suit.”

Nana waved her arms in disgust as she took a seat on the couch. It was an ongoing argument in our house. My dad wanted me to be in afterschool activities pretty much every waking hour. He said it would make me well rounded and help me figure out what I was most good at—“my thing,” he likes to call it. Then, once I discovered what “my thing” was, I could focus on it and get great at it before applying to college.

That was the plan, anyway.

My mom didn’t care nearly as much as my dad did about that kind of stuff, but she trusted him, and usually went along with what he wanted.

Meanwhile, Nana and I thought the whole thing was a little crazy. I don’t even like swimming. I mean, swimming in a pool at a friend’s house on a hot summer day is one thing, but going to the Y after a long school day is not my idea of a good time. But my parents thought it was important for me to become a good swimmer. Just like they thought it was important that I study Chinese, play soccer, learn the cello, volunteer at Junior EMTs, and have a math tutor.

And that was just during the week. On the weekends, you could throw in Little League and youth orchestra.

I think maybe it’s because I’m an only child that my parents pay so much attention to me, and shower me with love, and help me find a gazillion ways to improve myself. Or maybe it’s because practically every parent in America is obsessed with making sure their kids are experts at every activity ever created by humans.

Whatever the reason, I was busy twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. And even though I didn’t like it, I accepted it. Just like most kids accept it. Because we’re too lazy not to.

Anyway, I got my bathing suit and off we went. I turned the car radio up, and my mom immediately turned it down.

“How was school today?”

“Alex Mutchnik decided it would be funny to tape my hair to the desk.”

My mom smacked the steering wheel. “I’m going to call his mother!”

“No, you’re not.”

She looked at me, which was a little scary, considering she was also driving the car at the time. She did that a lot. “That kid sounds like such a nightmare.”

“He is a nightmare, but he’s my nightmare, so let me deal with it. Your job is to watch the road, so you can drive to the Y without killing me.”

My phone buzzed. I didn’t recognize the number. Who would be calling me? The only person who ever really called me was Leo.

“Hello?”

“Hi, Jack? It’s Cathy!”

My heart did a weird little somersault. Cathy Billows. The prettiest girl in the entire state, last I checked. Calling me! My first thought was that she needed help on a homework assignment or something.

I tried to play it cool. “H-hey, Cathy. Wh-wh-what’s going on?” Playing it cool is hard, it turns out.

“Not much!” Cathy is one of those girls who always talks in exclamation points. “How about you?”

“I’m on my way to swim class.”

“Oh, awesome!” Not really, which we both knew. “Well anyway, Jack, I just wanted you to know that I’m having a party Friday night to celebrate the end of the school year, and I thought you might want to come!”

“Me?”

“Yup!” Cathy giggled. “Everyone in homeroom is invited, so we can tell stories about the whole year! You can tell a funny story or something, since you’re kind of funny. It’ll be great! Please come—it will be so much more fun if the whole class is there!”

“Oh, wow, that does sound like fun.” I think I must have turned some strange color right about then, because my mom looked at me—still driving, of course.

“Who is it?” she whispered, way too loudly.

“Watch the road,” I whispered back, turning toward the window.

I spoke quietly into the phone. “Well, um, I have to ask my parents, but yeah, I’d totally love to come.”

“Awesome! Bye!” And just like that, she was gone. A potentially life-changing conversation, over in less than a minute.

I put the phone in my pocket and prayed that my mom wouldn’t start firing questions.

“Who was that? What did they want?”

My prayers went unanswered.

“Nobody, and nothing.” We were almost there. I found myself actually looking forward to getting out of the car and going to swimming.

“Oh come on, tell me,” badgered my mom. “It sounded like a girl.”

“I don’t want to talk about it right now, okay?” The truth was I didn’t want to talk about it ever. Because I already knew there was a problem with Cathy’s invitation, and I was pretty sure there wasn’t a solution.

My mom sighed. “Okay.” She could be annoying sometimes, but when it came right down to it, she respected my privacy. She’s pretty cool that way, I guess.

When we got to the Y, I hopped out of the car before my mom could think of any more questions.

“See you in an hour,” I said, sprinting up the steps.

I could barely hear her say, “Okay, honey. I love you,” before the door closed behind me.

3

I don’t need to bore you with the details of my swimming class. All you need to know is that we concentrated on the backstroke, which happens to be my least favorite stroke. I’m not sure how mastering the backstroke is going to help me get into a good college. You’ll have to ask my dad that one.

And I definitely don’t need to bore you by talking about the session I had with my math tutor after swimming. Technically, I suppose it could help with the college math test I’ll need to take in high school. Unless I forget everything, which, considering the test is about five years away, is entirely possible.

So let’s get right to the unboring part.

The night started out pretty much like every other night. My dad came home at his usual time, meaning after my mom and I had finished dinner. (Dad has a job in “overseas markets.” I have no idea what that means except for the fact that he works a lot. So does my mom, even though she doesn’t have a job job.)

Dad sat down to dinner, and Nana joined him.

“When are you going to admit that the president is doing a lousy job?” Dad asked her.

“As soon as you admit your guy would have been ten times worse,” Nana answered.

Then they proceeded to argue ab

out politics the entire meal, the way they do every night. They love every second of it.

After dinner, my mom and my dad sat down on the couch to watch TV while rubbing each other’s feet. That was also a nightly ritual—and it was the only time I ever saw them completely relax. Nana thought it was adorable. I thought it was kind of gross.

I decided to make my move halfway through their TV show, when they would be at their peak of relaxation.

“Mom? Dad? I have a question.”

My dad put the show on pause.

“What’s up?” asked my mom.

“Well, I got a call today from Cathy Billows, who’s like this really popular girl in our school.”

“I hate that word,” said my mom, meaning popular. She was the type of person who wanted all kids to be popular.

My dad looked curious. I didn’t get a call from a popular girl every day. Or any girl, for that matter.

“What did she want?”

“Well, that’s the thing,” I said, shuffling my feet. I was nervous, probably because I knew what was coming. “She invited me to her party Friday night. It’s kind of a big deal. I really want to go.”

My dad leaned back on the couch with a big sigh. “Well, that’s bad timing. You have your cello recital Friday night, which obviously you can’t miss.”

I felt my whole body get stiff. “Why not? Why can’t I skip the recital, just this once?”

“You can’t skip the recital,” my dad said. “I don’t care if the president himself invited you to the White House. You made the commitment to the cello, and this recital is the most important event of the year.”

I flopped down on a chair. “I didn’t make the commitment to the cello, you did!”

My mom looked at my dad. “Honey, maybe just this once—”

“Not just this once,” my dad said, the volume of his voice starting to increase just a bit. “He goes to the recital, and that’s it!”

Maddie hated fighting, so she gave a worried little bark and left the room. Nana, on the other hand, never missed a fight, so she came in.

“I can’t believe this,” I said. “This is ridiculous. I never get to do anything I want to do!”

A Zombie Ate My Homework

A Zombie Ate My Homework Rivals

Rivals Fangs for Everything

Fangs for Everything Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Making Money

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Making Money Pete Milano's Guide to Being a Movie Star

Pete Milano's Guide to Being a Movie Star Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Growing Up

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Growing Up The Real Us

The Real Us Game Changer

Game Changer My Dog is Better than Your Dog

My Dog is Better than Your Dog Katie Friedman Gives Up Texting!

Katie Friedman Gives Up Texting! Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Planet Girl

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Planet Girl Dog Day Afterschool

Dog Day Afterschool Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Reading

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Reading Charlie Joe Jacksons Guide to Summer Vacation

Charlie Joe Jacksons Guide to Summer Vacation Jack Strong Takes a Stand

Jack Strong Takes a Stand It's a Doggy Dog World

It's a Doggy Dog World