A Zombie Ate My Homework

A Zombie Ate My Homework Rivals

Rivals Fangs for Everything

Fangs for Everything Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Making Money

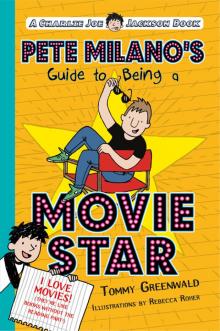

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Making Money Pete Milano's Guide to Being a Movie Star

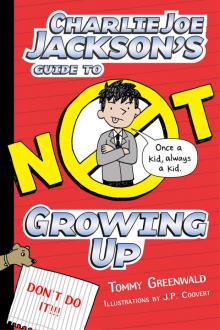

Pete Milano's Guide to Being a Movie Star Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Growing Up

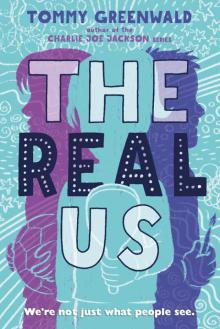

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Growing Up The Real Us

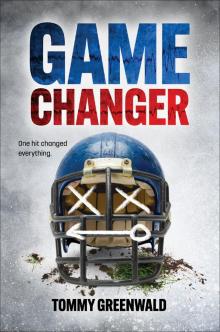

The Real Us Game Changer

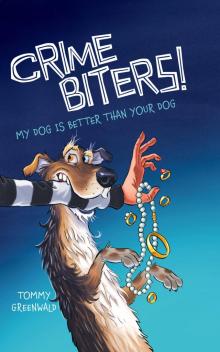

Game Changer My Dog is Better than Your Dog

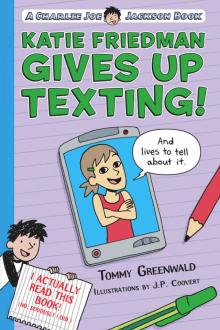

My Dog is Better than Your Dog Katie Friedman Gives Up Texting!

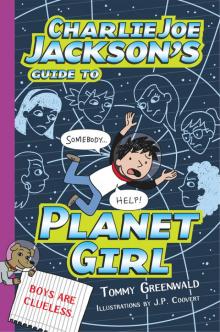

Katie Friedman Gives Up Texting! Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Planet Girl

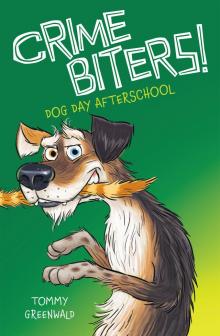

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Planet Girl Dog Day Afterschool

Dog Day Afterschool Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Reading

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Reading Charlie Joe Jacksons Guide to Summer Vacation

Charlie Joe Jacksons Guide to Summer Vacation Jack Strong Takes a Stand

Jack Strong Takes a Stand It's a Doggy Dog World

It's a Doggy Dog World