- Home

- Tommy Greenwald

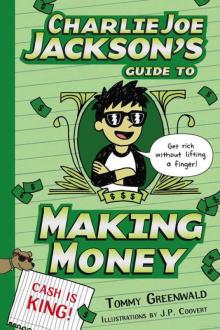

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Making Money Page 4

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Making Money Read online

Page 4

Charlie Joe’s Financial Tip #3

IF YOU HAVE TO WORK, MAKE SURE IT INVOLVES SOMETHING YOU REALLY LIKE.

I’m not an idiot. I know that eventually everyone has to get some kind of job. That’s the way the world is. But that doesn’t mean you have to hate it. There are lots of jobs out there that are awesome. Here are a few that I plan on checking out:

1. Ice cream store scooper

2. Movie theater usher

3. Bakery cupcake taster

4. Video game designer

5. Carnival ride tester

6. Television show reviewer

7. Book editor (KIDDING! Just making sure you were still paying attention.)

Part Two

THE SHIRT AND THE TIE

17

Hi, it’s me again. Katie Friedman.

I’m writing another chapter because Charlie Joe said it was the least I could do after his canine catastrophe.

Whatever. It’s kind of fun, so why not?

Anyway, he called me up right after it happened and said, “Your streak of never being wrong is officially over.”

Before I could answer, he added, “And when you’re wrong, you’re really, really, REALLY wrong.”

Then he told me the whole story, and I guess I was pretty wrong. But there was something about the way he blamed me for the whole thing that made any sympathy I might have felt for him disappear. So I listened, I tried not to laugh, I laughed anyway, tried not to laugh harder, laughed harder anyway, and then eventually I had to put the phone down because I was laughing so hard that tears were coming out of my eyes.

“Katie? Katie, are you there?”

I got myself together and picked up the phone. I was able to say, “Wow, Charlie Joe, that sounds like a total—” before I collapsed in a fit of giggles.

He hung up.

Now, we all know how fragile a boy’s ego can be, so instead of doing what I wanted to do, which was to let him stew and fret and realize he shouldn’t blame other people for his own mistakes, I called him back and tried to play nice.

“Charlie Joe, I’m sorry I gave you bad advice. I said you should dog-sit because you love dogs and I thought it might be fun for you. I guess that was a bad idea.”

He snorted. “A bad idea? That’s the understatement of the century.”

That’s what I get for trying to play nice.

And when he tacked on, “You just might want to keep your ideas to yourself for the time being,” my patience wore out completely.

“Listen, Charlie Joe,” I said, “all I said was that you might want to consider dog-sitting as a business opportunity. I never said take six dogs to Lake Monahan. I never said let them off the leash so they can run wild all over the park and scare a poor defenseless animal half to death. And I definitely never said bring Timmy into the operation, so you can secretly try to get him to do all the work while you just sit around counting your money.”

That last part might have been a little unfair, but I didn’t care. I was on a roll.

“So the next time you need a little bit of advice,” I went on, “there are plenty of people you can call. Call Pete. Call Nareem. Call Jake. Call Eliza. I’d say call Hannah, but since we both know you can’t form an actual complete sentence whenever you’re in her presence, that’s probably not such a good idea.”

I took a deep breath and waited. Silence.

“Charlie Joe?”

“I’m here. What do you have against Hannah? Are you jealous or something?”

Now, putting aside the fact that I hadn’t said anything negative at all about Hannah—all my insults were aimed squarely at Charlie Joe—it just so happens that I think Hannah Spivero is a great person, and I wasn’t jealous of her in the slightest.

“I’m not jealous of Hannah Spivero in the slightest,” I said, “and besides, I have band rehearsal, so I have to go.”

I immediately realized the second part of that sentence had nothing to do with the first. I hate it when that happens. It means I’m no longer in control of the conversation.

Charlie Joe laughed, a tiny little laugh, but just enough to let me know that he thought he won that particular round.

“Okay, fine,” he said. “Based on recent results, you should probably stick to music anyway, instead of trying to become a professional advice-giver.”

“Stick it, Charlie Joe,” I said, and hung up the phone.

Sometimes it’s good to go back to basics.

18

I think it says a lot about me that I’m willing to let Katie write chapters—in MY book—that make me look kind of like a jerk.

I just wanted to say that publicly.

We can get back to the story now.

19

At dinner after the doggie disaster, when my mom told my dad all about it, the first thing he did was ask if all the animals were okay.

Then, when he found out they were, he laughed for about eighteen minutes straight.

Then he stopped laughing, looked at me, and said, “This isn’t funny.”

It’s not?

“Money doesn’t just grow on trees, as they say,” Dad went on. “You have to work for it, and working is serious stuff. You can’t decide that just because you need money and like dogs, you can become a professional dog-walker.”

“Dog-sitter,” I corrected.

“Whatever. The point is a job is something you have to prepare for, and take extremely seriously.” He pointed at his briefcase, which was sitting by the door. “You think I just decided one day I wanted to be a lawyer, and the next day I went in front of a judge trying cases?”

“If you love being a lawyer so much,” I asked, “then why do you drop your briefcase the second you walk in the door, and change out of your suit like you’re allergic to it or something?”

“Watch it,” he said, but I could tell by his face that he thought I had a point. “I didn’t say I loved being a lawyer. I said I take it seriously because it’s my job. Working is hard, that’s just a fact of life, and the sooner you realize that, the better.”

Then he clapped his hands together, which meant he had an idea, usually one that I wouldn’t like.

“Hey, you know what? You should come to work with me for a day. Then you could see what getting a paycheck actually means.”

I laughed. “Yeah, well the thing is, I have this little thing called school, so sadly that’s not going to work out.”

“You don’t have school this Friday,” my mom pointed out unhelpfully. “It’s teacher development day.”

Now, usually I loved teacher development day, like all kids, but suddenly I realized how ridiculous it was. What was it that teachers were constantly developing anyway?

“Ugh,” I said, while I tried to think of another excuse not to go.

“I’ll give you twenty bucks,” my dad offered. “Think of it as a one-day, paid internship.”

Hmm. Twenty bucks. No gophers. It could be worse.

“Fine,” I said. “Whatever.”

My dad chuckled. “See? Money always has the last word.” Not really, since he was still talking. “We’ll take the train in, hang out at the office, grab some lunch—we’ll have a great time. And you’ll see what it really means to be a working man.”

“That sounds like a splendid idea,” my mom said, which was weird, since she never used the word splendid.

“Sorry I’m gonna miss it,” my sister, Megan, chimed in, finally joining the conversation.

Then she winked at me, which I didn’t appreciate.

Charlie Joe’s Financial Tip #4

THERE’S NO SUCH THING AS A FREE RIDE, UNLESS YOU KNOW SOMEBODY.

Isn’t it awesome when your dad, or your friend’s dad, or your friend’s mom gets free tickets to a game, and they want to take YOU? It’s awesome because you know that if the tickets are free, then the seats are great. Because free things are always the best.

That’s why it’s so important to know someone who has access to free thi

ngs.

The thing is, you can go through life one of two ways. You can work real hard and save up enough money to buy a seat in the upper deck. Or you can make sure you have a friend who will invite you to sit behind the third-base dugout.

It’s totally up to you.

20

The first fight my dad and I had on “take your unlucky son to work day” was about what I was going to wear.

As soon as my dad told me I had to wear a tie, I demanded a raise to forty dollars.

“Denied,” said my dad.

“No way!” I argued. “You know how the skin on my neck is so sensitive? How I get those rashes all the time?” He looked at me blankly, so I added, “A tie could quite possibly kill me.”

Dad sighed the first of what would turn out to be many sighs that day and quickly decided that this was not a fight he wanted to have. “Fine, just wear a decent shirt that doesn’t have a picture of a death metal band on it.”

You may have thought I won that fight, but I didn’t, since I still had to wear long pants.

The train was packed. I thought I liked my cell phone, but you should have seen these people. It’s amazing they weren’t all in neck braces, the way they stared down at their phones and iPads, typing away. There were even a few people actually talking on their phones, which apparently is a big no-no, based on the looks they were getting.

I slept on the train, obviously, since I’d woken up approximately five hours earlier than usual. I like to sleep until noon on non-school days. Doesn’t everybody?

* * *

The walk from the train station to my dad’s office was about ten minutes, which was nine minutes too long. The office was really fancy. It had a lot of desks, which happens to be my least favorite kind of furniture. There were tons of people running around looking busy, phones were ringing constantly, and there were books everywhere (scary!).

My favorite room in the office was definitely the kitchen, which had a huge candy jar and free soda.

The first thing my dad did was introduce me to all the people. I could tell who were the ones who worked for him by how enthusiastically they greeted me: “Great to meet you, Charlie Joe!” or, “So this is the Charlie Joe I’ve heard so much about!”

Then I met his boss, Mr. Felcher, who looked kind of like a mean version of my grandfather. He was on the phone, so he just looked up and waved, kind of like he was swatting a fly. Then he put his hand over the phone and whispered, “Make sure your old man puts in a full day’s work.”

Dad laughed like it was the best joke that had ever been told on the planet.

I also met my dad’s assistant, Sheila, who wore glasses around her neck. The only other person I’d ever seen do that was Mrs. Sleep, the principal at my school. Sheila was one of these people who thinks you have to talk extra loud to kids, like English is our second language or something.

“WELCOME TO WEISSLER, SELLER, AND MCCOLLUM,” she said, overenthusiastically.

“Who?” I asked.

“That’s the name of the firm,” my dad clarified, before Sheila had the chance to rattle my eardrums again.

“Oh,” I said. “Are any of them around? I’d like to meet Weissler first, followed by Seller, and then McCollum.”

“They’ve all passed away,” my dad answered.

That seemed weird. Who would want to work at a company that was run by a bunch of dead guys?

“Mr. Jackson’s office, please hold,” Sheila said into the phone, before turning back to me. “NICE TO MEET YOU, CHARLE JOE. FEEL FREE TO COME TO ME FOR ANYTHING YOU NEED.” She was nice. I could see how working wasn’t so bad if you had someone around who would do anything you needed.

Maybe if you played your cards right, you could even get her to do the work for you.

Then two guys in suits and one woman in a woman suit came up to my dad.

“The brief and the motion and the verdict and the jury and the recess and the Judge!” they said. (Okay, I’m making that up—I don’t exactly speak lawyer. But there was some sort of emergency—that much was clear.)

“Guys, give me one minute,” my dad said. He turned to me, trying to figure out how to put me to work. Then he looked around his office and spotted a huge stack of papers about a mile high. Then he looked at me again.

“No way,” I said.

“Charlie Joe, I need you to look through that document and find all the references to Furman v. the State of Missouri, circle them, and put a Post-it note on those pages.”

Furman v. the State of Missouri? It sounded like a boxing match. And not a very fair fight.

“How long will that take?” I asked.

“Should take us right up until lunch,” my dad said, gathering up a bunch of papers and books and notes and hurrying out the door. “We’ll go someplace delicious, I promise.”

“THERE’S A CHINESE PLACE RIGHT AROUND THE CORNER THAT I LOVE,” Sheila screamed.

Well, that’s good. Two hundred pages of lawyer stuff seemed a little less painful, knowing that a big plate of sesame chicken would be waiting on the other side.

21

I don’t want to bore you by talking about how boring Furman was, and how boring the State of Missouri was (sorry Missouri people, I’m sure it’s not your fault), and how I was so bored I started having little conversations with each piece of Post-it paper I used. (“There you go, little Posty, have a nice life on page seventeen.”)

All you really need to know is that after about twenty pages (out of 237), I fell fast asleep on my dad’s couch. I think I may have drooled a little bit on his pillow. It was a swell nap, until I was woken up by a sharp poke in the ribs.

Dad’s boss, Mr. Felcher.

“Hard at work, I see,” he grumbled. I figured I was supposed to laugh, so I did. But Mr. Felcher didn’t seem all that amused. “Where’s your father? We’ve got a problem.”

“He went to judge a pair of briefs, or something like that,” I said. Then I noticed Sheila standing at the door. She had that expression on her face that you see when people are watching a horror movie, and they don’t want the cute girl to open the door to the basement.

“Judge a pair of briefs?” the old guy barked. “What does that even mean?”

My dad came running into the room. He saw three things that didn’t exactly make him jump for joy: me lying on his couch, a drool mark on his pillow, and his boss perched over me like a mean, old crow.

“Were you looking for me?” my dad asked Mr. Felcher, but the old guy stomped away.

“We’ll talk later at the partner meeting,” he yelled back over his shoulder.

My dad stood there for a second, then slowly sank down on the couch next to me.

“I found thirteen Furmans before I fell asleep,” I said, trying to look on the bright side.

“Maybe I should go into the dog-walking business,” he answered.

* * *

We went to Sheila’s Chinese place for lunch, where my dad tried to get mad at me for passing out on his couch. His heart wasn’t in it, though, I think because he realized that no kid should be able to read a 237-page legal document without falling asleep at least six times.

Then he launched into a long story about how he wanted to be a writer when he was younger, but when he met my mom he realized he had to get a real job, so he went back to law school and became a lawyer, and usually he really likes it but sometimes he doesn’t, but either way it’s his job and he takes pride in how hard he works at it because our family depends on him, and my mom works just as hard at home because the family depends on her, too, and the sooner I realized the value of hard work, the better off I would be later in life.

I was too busy enjoying my sesame chicken to pay close attention, but I suddenly heard him loud and clear when he stopped talking.

He looked at me. “What do you think?”

I wasn’t sure what exactly he was referring to, so I said the first thing that popped into my head.

“I think it’s delicious.”

He glared at me. “Did you even hear a word I said?”

This time he was able to stay mad.

22

My dad and I walked back to his office without talking, and when we got upstairs he said, “Just wait here and do whatever you want while I go to this meeting, then as soon as it’s done we’ll go home. Don’t break anything.”

I felt a little guilty that he didn’t think I could last a whole day at his office, but I felt a lot psyched that I didn’t have to spend a whole day at his office.

After about twenty minutes killing time on my dad’s computer playing video games, my cell phone rang.

“Hey, Mom.”

“Hi, honey! I need to ask Daddy a really important question, and he’s not answering his phone. Is he with you?”

I knew he was in a meeting, but my mom needed him, and besides, I was looking for something to do. “I can find him, hold on.”

I walked down the hall, peeking in rooms and offices, but no luck. Then I saw a door that said CONFERENCE ROOM and I remembered that he said he had a meeting. As far as I knew, meetings were probably like conferences, and they probably happened in conference rooms.

So I went in, and there he was. Along with about twenty other people, including Mr. Felcher.

They were all really, really dressed up, and they all looked really, really serious.

My dad looked up, saw me, and immediately turned the color of a tomato.

“What do you need, Charlie Joe,” he said, although he didn’t even really open his mouth when he said it.

“Um, Mom wants to talk to you.”

My dad closed his eyes and took a deep breath. “Not now.”

“Dad can’t talk right now,” I whispered into the phone, and hung up.

Just then Mr. Felcher smacked the laptop that was in front of him and said, “Damn these things!”

Well, that was kind of cool that he swore, but nobody else seemed to think it was all that cool, because everybody got even quieter, and they had all been pretty silent to begin with.

A Zombie Ate My Homework

A Zombie Ate My Homework Rivals

Rivals Fangs for Everything

Fangs for Everything Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Making Money

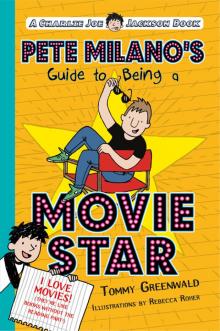

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Making Money Pete Milano's Guide to Being a Movie Star

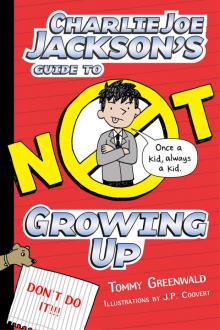

Pete Milano's Guide to Being a Movie Star Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Growing Up

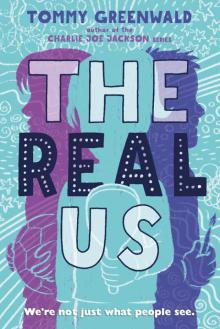

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Growing Up The Real Us

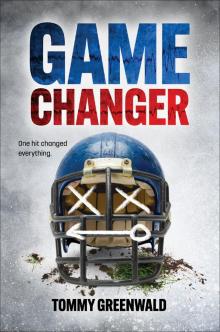

The Real Us Game Changer

Game Changer My Dog is Better than Your Dog

My Dog is Better than Your Dog Katie Friedman Gives Up Texting!

Katie Friedman Gives Up Texting! Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Planet Girl

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Planet Girl Dog Day Afterschool

Dog Day Afterschool Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Reading

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Reading Charlie Joe Jacksons Guide to Summer Vacation

Charlie Joe Jacksons Guide to Summer Vacation Jack Strong Takes a Stand

Jack Strong Takes a Stand It's a Doggy Dog World

It's a Doggy Dog World