- Home

- Tommy Greenwald

A Zombie Ate My Homework Page 3

A Zombie Ate My Homework Read online

Page 3

There was a buzzing in my ears, like the sound of the microwave that Jenny uses to heat up her coffee. “Can I … uh … why is it so hard for me to remember anything before the escape?”

Bill shrugged gently. “Well, I don’t believe you were designed to have much of a memory. And when you fell into that ditch, you avoided being captured, but you also got a good knock on the head. Might have knocked the few memories you did have clear out of you.”

“Oh,” I said.

“I’m very sorry, Norbus.”

I didn’t have much to say after that. I didn’t feel sad, or nervous, or scared.

I just felt alone.

Bill stood up. “Now, as I’ve said, no one knows you’re here with us, and I’d like to keep it that way. Which is where the next part of our conversation comes in.” He walked over to a large bookshelf that was above the TV and pulled down a book. “This is a little awkward, but I have to ask you something. Can you read?”

I blinked. “Can I read?”

“That’s right.” Bill opened up the book. “Now, I know you have a strong vocabulary, so you’re obviously very bright, but I have no idea if you’re a reader.” He looked down, a little embarrassed by the conversation. “Are you, son?”

“I don’t know,” I told him. “I can’t remember.”

“Well, let’s find out, shall we? Why don’t you go on over and pick out a book.”

I picked up a book called War and Peace. It was so heavy it practically fell out of my hands.

“Seriously?” said Bill. “Why that one?”

“I don’t know,” I said again.

“You might want to—” began Bill, but he didn’t finish his sentence, because by then I was already flipping the pages as fast as I could.

Sixty seconds later, I looked up. “This isn’t really my kind of book, to tell you the truth.”

Bill glanced down at the page I was on and his eyes went wide. “Are you trying to tell me you just read forty-seven pages?”

I nodded. “It’s clear that the author is a great writer, but all those Russian names are very confusing.”

As I struggled to put the heavy book back on the shelf, Bill laughed. “Well! I knew you all were smart, but I guess I didn’t realize quite how smart.”

I suddenly felt shy and stared down at my hands. They looked incredibly white, and you could practically see right through to the bones. Now that I was seeing humans up close all the time, with their deep, rich coloring, I realized how completely different we were.

“Anyway, Norbus, there’s a reason why I asked you about reading.” Bill held up the book he’d been holding in his hand. “This is a book of names. I’d like to find you a new name, one that won’t draw any unwanted attention. A more normal name.”

“I think my name is normal.”

“I think you know what I mean.”

After a few seconds, I shrugged. “Any name is fine.”

“I’d like you to pick it out.” Bill brought the book over to me. “Now remember, this is the name you’re going to live with, possibly even for the rest of your days. You need to find something that makes you comfortable.”

“Okay.” I wanted to get this over with as quickly as possible, so I turned to the first page of the book and pointed without even looking. “That one.”

He peered down. “Arnold? You want your first name to be Arnold?”

“Yes.”

“Fine. Arnold Kinder it is.”

I was confused. “Kinder? What’s wrong with Clacknozzle?”

He sighed. “Again, it will just make you stick out like a sore thumb. We don’t want that.”

“But I am a sore thumb,” I said. “I won’t fit in, no matter how hard I try. I don’t look like you, and I never will. I look like me.”

“Norbus,” said Bill in a gentle voice, “I realize how difficult this must be for you. But I want to assure you of one thing. This is all just to make life easier for you. Yes, you have to fit in to our society, but that doesn’t mean you’re giving up your true identity. And it doesn’t mean you have to stop being who you really are.”

I looked at him, feeling the heat of my red eyes burning through my cold white skin. “I don’t have to give up my true identity?”

“Absolutely not.”

“Fine.” I handed the book back to Bill. “Then I would like my last name to be Zombie.”

Bill laughed, in a short, loud burst. “HA!” But then he looked at me, and he realized I was serious. “Norbus, you can read a thousand-page novel without breaking a sweat. I would think someone with your level of intelligence knows why that can’t happen. And besides, we are going to tell people you’re related to us; so obviously, your last name should be Kinder. Surely you understand.”

I did understand, of course. But I didn’t care. After a while, you realize which are the things that matter. The things that are important enough to make you say to yourself, Without this, nothing is worth fighting for.

“You said I don’t have to stop being who I really am.”

“That is true,” Bill admitted.

“Well, this is who I am.”

Neither of us said anything for a few seconds, then I had an idea. “How about if we spell it differently? Z-O-M-B-E-E. That way, no one will suspect anything.”

“You can’t really believe that.”

“It’s what I want.”

“You are one stubborn young man.”

We both stared at each other for a few seconds. Then I said, “Okay then, how about this: We’ll make my middle initial Z, and my last name O-M-B-E-E?”

Bill threw up his hands. “For gosh sakes, we may as well keep Clacknozzle!”

“Somebody else named me Clacknozzle,” I told him, “so now that I think about it, that’s not who I really am either. You said I get to name myself this time. Well, I would like my last name to be Ombee.” I paused for a second, then added, “That’s my final offer.”

Bill looked at me like he was both annoyed and impressed. We both knew how silly it sounded. We both knew how crazy it was. And we both knew that there was no way I was going to change my mind.

Bill stuck out his hand, and I shook it. Then he patted me on the back.

“Nice to meet you, Arnold Z. Ombee.”

“Are you ready?” asked Bill.

I wasn’t sure how to answer that.

Is a zombie ever really ready for fifth grade?

When I went downstairs that morning, after spending the night in my room thinking and reading, the first thing I saw was a note from Jenny.

Had to go to work. Look forward to a full report tonight. Aunt Jenny.

I stuck the note in the pocket of my brand-new, incredibly uncomfortable shirt.

Bill was in the kitchen, making breakfast for Lester. When he saw me, he clapped his hands together. “Holy smokes, Norbus—I mean, Arnold—you look great!” He walked over and handed me my notebook. “Are you ready? Are you feeling okay? Did you get some rest? Do you need anything? Are all your supplies in your backpack? Did you remember your pencils? Do you want to go over everything again?”

I took a deep breath. “Maybe one more time.”

Bill sat down in front of me.

“Who are you?”

“I’m Arnold Z. Ombee, your nephew, and I’m here because my parents had to move overseas for six months.”

“Why are you so pale?”

“I have a skin condition and can’t go in the sun.”

“Why can’t you play sports?”

“I have a muscle mass deficiency.”

“Why can’t you eat most foods?”

“Allergies.”

“Do you have your doctor’s note?”

I got the note out of my pocket and unfolded it.

I looked up at Bill. “Who’s Doctor Jonas again?”

“A family friend.”

“Oh.”

He smiled. “All righty, then. People are going to think you should be in a plastic bubbl

e, but that’s okay.” He was trying to make a joke, but I could tell how worried he was.

“I’ll be fine,” I told him. “I will.”

The truth was, I was scared.

“You’ll be great, I know it,” Bill said. “And if you get nervous, just take a few deep breaths, it will calm you right down.”

“Uh, okay.” I didn’t have the heart to remind him that I don’t breathe. At all. Ever.

Lester started drumming his hands impatiently on the table. “Let’s GO! We’re gonna miss the BUS! Come on, Arnold Z. Ombee.” He said it like it was the dumbest name ever.

He may have had a point.

Bill gave me a big hug. I felt my cold bones melt a little in his arms.

“Go get ’em,” he said.

Lester held the door open as we walked outside. He quickly caught up to me and smacked the notebook out of my hands. As I bent down to pick it up, he leaned over me. I could smell the Sweet-A-Ramas on his breath. “Get used to people doing stuff like that to you,” he said. “You’re the new kid, and you’ve got a target on your back.”

“Okay.”

“And remember, I’m in ninth grade and you’re in fifth,” he said. “So as soon as we get off the bus, you’re on your own. Here’s my advice: Keep your head down and don’t make anyone mad. And remember, no fancy words! Got it? If someone figures out who you are, you’re as good as dead.”

“Don’t you mean undead?” I asked him, trying to impress him with another joke—but he was already running, far ahead of me, and he didn’t look back.

The school bus was the scariest place I have ever been in my kind-of life. And I’m a zombie. I’m supposed to specialize in scary.

Lester ran straight to the back of the bus, where the older kids were. When I got on, the first person I saw was the driver. He didn’t look at me so that was okay. But then I turned and started walking down the aisle, and I suddenly felt like I was under a very unfriendly microscope. Kids stared at me with challenging eyes, as if they were daring me to try and sit next to them, just so they could tell me to get lost. Boys were elbowing one another, snickering and whispering stuff like “Get a load of the new kid” and “Looks like he moved here from Losertown.”

And the girls? Believe it or not, they were even worse.

They refused to look at me at all.

I felt sweat start to ooze out of my shoes as I walked up and down the aisle. Then for a few seconds I just stood there, trying to figure out what to do.

“Take a seat, dork,” I heard a voice say. “We can’t go until you sit down.” I realized the voice was right: The bus wasn’t moving, and all the heads had swiveled toward me, waiting.

Suddenly out of nowhere, I saw a girl move a few inches to her left. Was that an invitation?

I decided it was.

I dashed forward and plopped down next to the girl, who didn’t even glance at me. I leaned back, but it wasn’t very comfortable. Something was in the way.

“Your backpack,” said the girl, still staring straight ahead. “Take it off and put it under your seat.”

I did what I was told.

“Thanks,” I said. “This is my first day.”

“Duh,” said the girl.

I snuck a quick peek in her direction. Her skin was as dark as mine was light. She was wearing a blue dress and blue shoes. She also had a blue barrette in her hair.

“Do you like blue?” I asked her, like an idiot.

She covered her mouth and let out a short giggle. “Duh again.”

“My name is Arnold Z. Ombee,” I said, just to see how it sounded.

It sounded not so good.

The girl twirled her hair and let out a short, loud laugh. “That’s your name, seriously?”

“You can just call me Arnold,” I said, deciding then and there to only use my first name from that point on. “Thank you for making room for me so I could sit here. That was very magnanimous of you.”

“Very what?”

I silently yelled at myself for using a four-syllable word. “It was nice of you. Very nice.”

“Oh. Yeah, it was nice, you’re right.” She turned her head and looked at me for the first time. “Why are you so pale?”

That’s when a normal human boy would blush. But not me.

“I— I have this skin condition where if I’m in the sun too long, I break out in terrible rashes and hives. It’s like an allergy. So I stay indoors most of the time.” Like my name, the explanation had sounded a lot better at home; now that I was saying it out loud to a real live actual human girl, it felt extremely—what’s the word Lester would use?—oh, yes. Uncool.

I waited for the girl to laugh in my face, but instead she just shrugged. “Oh, I’m sorry. That’s too bad. I love being outside. My name’s Kiki.” She looked out the window and started singing to herself.

“What song is that?” I asked, but she just smiled.

I took that as a sign that the conversation was over.

The girl named Kiki kept singing, and I was minding my own business, waiting for the bus ride to end, when I felt a flick on the back of my neck. I ignored it, thinking I must have imagined it, until I felt it again, a little harder this time. It was definitely a flick all right, caused by a human finger.

I turned around.

A boy was sitting there by himself. His face was red, his eyes were little slits of blue, and his black hair stood up in short, angry spikes.

“Yo,” said the boy. “What are you looking at?”

“Well, you’re flicking my neck with your finger, and I’d like you to stop it, please.”

“You’d like me to stop it??” He stood up. “Did you hear that, everybody? Ghostie here would like me to stop it!”

“My name is Arnold,” I said, trying to sound convincing.

The red-faced boy snickered. “Yeah, but you’re white as a ghost, so Ghostie it is.”

“Hey!” rumbled the bus driver. “Knock it off back there.”

The boy sat back down, and I turned back around to face the front. I glanced over at Kiki, hoping for a little smile that might make me feel better, but she was still looking out the window and humming.

FLICK!

It was the hardest one of all.

“Ghostie!” the Flicker said. “Why is your skin so cold?”

But before I could give him another rehearsed answer—I have a circulatory issue, my blood pumps more slowly than normal people—Kiki turned around and flashed her brown eyes at the Flicker.

“What?” he moaned, suddenly looking guilty.

“Stop calling him Ghostie,” she said. “He said his name is Arnold.” Then she looked at me and winked. “Right, Ghostie?”

The good news was, everyone laughed, including the Flicker, and I didn’t have to worry anymore that I was going to get beat up before the first day of school even started.

The bad news was, I had a new nickname.

“Can I have everyone’s attention?” the teacher said. “We have a new young man in school today. Let’s make him feel welcome.”

Well, if that isn’t an invitation to make fun of someone, I don’t know what is.

I was standing in the front of the classroom, having just handed my principal’s note to the teacher. The teacher’s name was Irma Huggle, which made me wonder why I had to change my name from Norbus Clacknozzle.

“Please give a warm Bernard J. Frumpstein Elementary School hello to”—Mrs. Huggle glanced down at the note—“Arnold Z. Ombee. Spelled O-M-B-E-E.”

At the announcement of my “name,” the other kids—who had been slouched over, barely looking at me—suddenly sat up straight as arrows and started murmuring a mile a minute.

“Ombee?”

“Is he serious?”

“What kind of name is that?”

“Shush!” commanded Mrs. Huggle. She gave me a friendly smile, which made me feel better. “Please take the open seat next to Mr. Brantley.”

I glanced over to where she was p

ointing. Care to guess who Mr. Brantley was?

You got it. The Flicker.

I walked slowly to my seat. The Flicker was grinning like he’d just won the lottery, which, according to the commercials I’d seen on television, was a very good thing. Everyone else was staring at me with their mouths open, as if the combination of a new kid, a weird name, and see-through skin was too much to take. I couldn’t blame them. I would have been fascinated and a little creeped out by me, too.

“Hey, Ghostie,” said a girl’s voice, and I glanced over. Kiki, my seatmate on the bus, was in the row in front of me, smiling.

“Hi, Kiki,” I said. I pointed at the Flicker. “Should I ask the teacher if I can move?”

“Only if you want to immediately become known as the wimpiest wimp in the class.” She giggled. “Anyway, Evan’s harmless. We’ve been friends since, like, forever.”

“You have?” I glanced over at the Flicker—whose name was apparently Evan—and suddenly he didn’t seem so bad.

“Yup,” she said. “Anyway, find me at lunch.”

A weird feeling filled my body—but not a bad weird feeling, a good weird feeling. “Okay, I will.” I noticed Kiki was humming to herself again. “Why are you always singing?”

She shrugged. “I’m not sure. Maybe because it makes me happy, or maybe because I’m always happy. One or the other.”

I thought about that for a second. I wasn’t sure what being happy felt like. Maybe someday I could be happy, too.

Then I sat down, just in time for Evan to flick me in the neck one last time.

“Looks like we’re neighbors!” he exclaimed, still grinning that grin.

That did not make me happy.

As soon as I realized that you were supposed to raise your hand if you knew the answer to a question, I raised my hand whenever Mrs. Huggle asked one.

“Yes, Arnold?” Mrs. Huggle would say.

“The capital of North Dakota is Bismarck.”

“Very good.”

A few minutes later, I realized that if you raise your hand every time the teacher asks a question, and you actually know the right answer, the other kids will find you irritating and obnoxious.

A Zombie Ate My Homework

A Zombie Ate My Homework Rivals

Rivals Fangs for Everything

Fangs for Everything Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Making Money

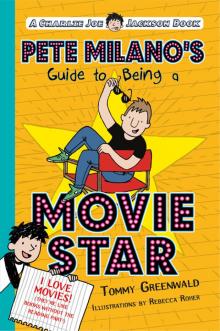

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Making Money Pete Milano's Guide to Being a Movie Star

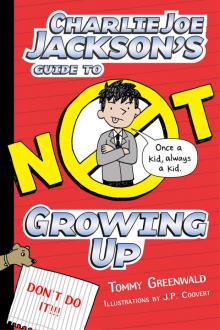

Pete Milano's Guide to Being a Movie Star Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Growing Up

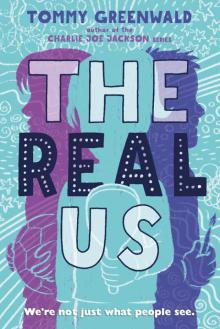

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Growing Up The Real Us

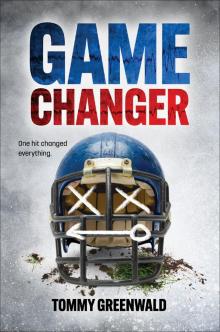

The Real Us Game Changer

Game Changer My Dog is Better than Your Dog

My Dog is Better than Your Dog Katie Friedman Gives Up Texting!

Katie Friedman Gives Up Texting! Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Planet Girl

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Planet Girl Dog Day Afterschool

Dog Day Afterschool Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Reading

Charlie Joe Jackson's Guide to Not Reading Charlie Joe Jacksons Guide to Summer Vacation

Charlie Joe Jacksons Guide to Summer Vacation Jack Strong Takes a Stand

Jack Strong Takes a Stand It's a Doggy Dog World

It's a Doggy Dog World